A Brief History and Look at Future Trends in US Craft Beer

Saturday, February 17th, 2018

“Beer is more important than armies when it comes to understanding people.” – Alexei Vranich

An Early History of Craft Beer

Early American beer started with ales from the British settlers; porters, stouts, and pale ales (once kilning took hold as general practice in 1703). It is common knowledge that most of the founding fathers were homebrewers, with George Washington being one of the most famous of them. One thing that many people don’t talk much about is the role of women in early American brewing. These brewing maidens many times managed their own operations, brought communities together, and many were also typically bakers as well. They kept cats as house pets, and hung their brooms outside their houses to signify that beer was flowing. Recognize anything familiar? These women were demonized by Puritan settlers to promote staunch temperance, and thus the “witch” was born.

Once German settlers started arriving in the later 1700s and 1800s, lager beers came into the forefront. What we saw after that was a hybridization of style—basically a blend of the lager and pale ale (especially in the warmer climates)—this is where the California and Kentucky common came from, as well as the cream ale. These were the standard beer menu items almost any domestic brewery carried. Locality had a lot to do with it. Just as it always has been in brewing, you use what’s fresh and what you can get your hands on. This is the reason the American adjunct lager became the popular method for brewing lager in the US, because local American 6-row Barley didn’t have the same gravity potential as European 2-row, so corn and rice were added to increase the available sugar content in the beer without changing the flavor too much. There are various research papers from the time that praised this innovation, which allowed everyone to continue drinking their favorite bubbly beverage. Around this time also (pre-18th amendment America), there were just a couple hundred breweries less than there are today. You could say it was in its own hey-day. Macro breweries had been at a disadvantage during this period, as the local brew pubs were the ones with the freshest selection and lower price that the larger players couldn’t compete with. Prohibition is what allowed for the large breweries to take over, they were the ones that invested in canning lines, distribution (trucks, etc.), and large facilities. They also brewed low alcohol/zero alcohol beers to stay afloat during that time or did things like selling malted milk to candy companies. I don’t really need to spend much time on what happened after that. One thing that is quite notable, however, is that even through this time, there were pub and brewery owners truly honoring the craft. This helped to create an underground community that eventually assembled the American Brewer’s Association which helped establish specific protections for independent breweries, and today is the driving force in beating back the macros of the world, creating a niche for these brands that are truly “craft.”

There really was a shift when the Cold War ended. The early 1990s saw people like the pioneers from Sierra Nevada and Dogfish Head come along and helped to truly reshape what American beer is, basically by saying, “this can’t be all there is…” They doubled down on their beliefs, and decided that the way to make it was not to do a better version of the American Light Lager, but to do something completely different. They followed the Henry Ford methodology, giving people something that they had no real expectation for nor basis of judgement- “If I had asked the customer what they wanted, they would have asked for a faster horse”. In today’s market, these same companies are working tirelessly to stay relevant and compete with the up-and-comers, who seem to have a strong pulse on the changing palate of the American beer drinker. Because of this innovation, the US is now the best place to try and taste new beers, according to Randy Mosher. Between 2015 and 2017, almost 1,000 breweries were opened, and in 2017 craft beer surpassed 10% of overall US beer market share (BeverageDynamics). People have come to demand new and local, something that Big Beer has been tapping into with their Shock Top/Blue Moons and Goose Island/Kona brands- falsely representing brands as craft when they are just as “big” as Budweiser itself. Certain large craft brands have also been seen adding products to the shelves to compete in the smaller craft brew space, e.g. Tropical Torpedo (Sierra Nevada), Voodoo Ranger/Citradelic (New Belgium), Rebel IPA and now a New England IPA (Sam Adams) to name a few. This is the one thing that makes me excited about the future of beer, as if these pioneers are basically a step behind now, where can this industry really go? Authenticity and taste will always seem to trump craft no matter how you define the word. We’re basically seeing history repeat itself- just with different flavors and style trends- and way larger marketing budgets.

There’s a lot of speculation of what’s to come. If 2018 is anything like 2015 or 2017, we’ll likely see another huge acquisition that blows everyone’s minds and makes the buy-outs of yester-year feel like a drop in the bucket. The one refreshing aspect of all of this is how gracious the beer drinking community is. Yes there are people who have had their egos get far too overinflated, but the fact remains that this culture is one based on trust and comradery. For every 10 new breweries, there is at least one homebrew store opening, and soon local malt houses will start to be a staple in the industry as up-and-comers look to distinguish their malt taste, reminiscent of what the French have coined “terroir”. One of the most interesting pieces I got my hands on was a research paper talking about the role that wasps will play in the future of beer taste, as wild yeasts can breed and mutate within the stomachs of wasps. Some larger craft breweries have been experimenting with “brewing history into the glass,” and I’m fascinated to see what type of concoctions brewers will continue to bring to the table in this “ancient” vein. Heck, I heard of a beer that was brewed from a yeast isolated from the brew master’s beard! Now that the science is more specifically understood, there will be some amazing flavors hitting the market that might make our hoppy berliners of today look like finger paintings next to these flavor Picassos. I just saw a well-produced social media ad for sour beers claiming they’re incredible for digestive health. I can see the marketing campaigns already… “So you like Kombucha… Then you’ll love this beer”- they’re already selling 7% abv Kombucha… so why not?

2017 in Craft Beer

Some Big trends that 2017 saw: sour beers, dry hopped wild beers, fruity/juicy IPAs, New England IPAs, and milk in everything. Even though people have loved to hate some of these trends, they’ve come about from brewers responding to feedback from their customers, by just giving the fans what they want. A very stark advantage that these up and coming breweries have is not being chained to successful brands, which frees up tap space for more seasonal brewing, and allows the brewers to pay more attention to their customers. Some tap houses have gained market share by never carrying the same keg twice.

One trend that seems to be gaining momentum is the alternative grains movement. In 2015, Business Insider listed gluten-free beer FIRST on its list of 4 trends to look out for in the coming years. I’m making no large, overarching comments here, but that could be the reason I was chosen to write this article (being a glutard myself). Certain breweries like Ghostfish and Glutenberg have gotten their flavors profiles down so well that we might see a day when gluten-free is no longer just for those with sensitive stomachs, or who are health conscious, and is lumped in with the rest as just down right good beer. It’s still made with water, malted grains, hops, and yeast. Speaking of the Reinheitsgebot, many countries, like Germany, are drinking 30% less beer per capita, and “health reasons” is the main driving force. Take this into account. The same year that the USA was rated the fattest country in the world (2007), Germany was rated as the fattest country in Europe. Gluten is an inflammatory protein. There’s not really any way around that, and gluten-reduced beer just carries chopped up gluten protein pieces, from which I personally still experience inflammation in the form of brain fog, sore joints, and worse hang-overs (think hangover turned flu-like), so there is a chance that gluten-reduced might not be a long-lived trend in beer. Lacking those inflammatory proteins, the path forward may include a growing number of gluten-free breweries, where grains that have typically been on the periphery will now take center stage, like millet, buckwheat, rice, sorghum, quinoa, oats (that are certified gf), corn, amaranth, sweet potatoes, beets, dates, and various of other malt-able grains and sugars. By no means has barley seen it’s day, but there is a massive potential for this industry to take flight considering that according to the National Foundation for Celiac Awareness, as many as 18 million Americans may have non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS).

Other Trends to Watch For

I’m very excited to see that barrel aging has gained so much popularity in beer. The next few years will likely see every commercial barrel used for any spirit being used to beer aging- Tequila and Rum barrels especially- the bourbon barrel/taste is starting to play itself out. Also, I’m starting to see less shaker pint glasses serving my favorite golden elixirs- which means that the education about what beer can be is getting out to the masses.

The public has spoken, as one-bottle wonders are typically a one-time sell. Some craft beer enthusiasts may be willing to pay extra for a beer that they’ve decided they’re going to try and check off their beer bucket list, but they’re not going to come back and buy your 18% ABV mother of all IPAs night after night. Session beers are making a strong comeback, especially as this local movement takes hold and breweries become communal gathering places again and not just destination visits for beer pilgrims. I also keep hearing about pilsners making the list at just about every brewery, so much so that even Robert Mondavi’s kid is opening a brewery that will specialize in just pilsners. Who would have thought? Either way, expect to start hearing from more Utah brewers to be leaders in this space (*throat clear* Jennifer Talley is a genius).

One thing that seems safe to say is that IPA’s are here to stay. Breweries will continue to have IPAs, and in some cases, have more than 4 IPA styles on their tap list (some are all IPA breweries and are not ready to admit it). In today’s climate, it’s almost expected. The number of new breweries being launched with an IPA as their flagship beer is almost staggering. To keep up with this demand, hop cultivars will continue to experiment and breed strains together to get the right chemical mixes and really make those flavors pop. We’ll be seeing some hop breeding relationships that will most likely blow people’s minds- think mixing two “not-as-popular” hops to create something far more desirable- this could change the taste styles we see.

Craft Beer Style Crossover

Speaking of breeding, beer styles have been getting it on so to speak; so much so that they don’t really have their own style category for judging. In fact, we’ll likely see so much style-creep that naming beers might become purely marketing. Cans are already starting to look like professional works of art with the labeling designs, and it’s working. Somehow asking for the bartender for a pint of the “Tropical Imperial Hazy Kolsch” just doesn’t seem like it’ll work in the long run. What do we really know anyway? Could the pilsner’s day actually be in its twilight of popularity? Whatever the case, quality will always win in the craft game.

“Tod Zum Reinheitsgebot” (Gluten Free India Dunkel Bock)

| Grains | Hop Schedule | Yeast |

|---|---|---|

|

|

WLP 833 German Bock Lager Yeast |

| By the Numbers: | ||

| OG:1.070 | FG:1.005 | ABV:8.5% |

Notes:

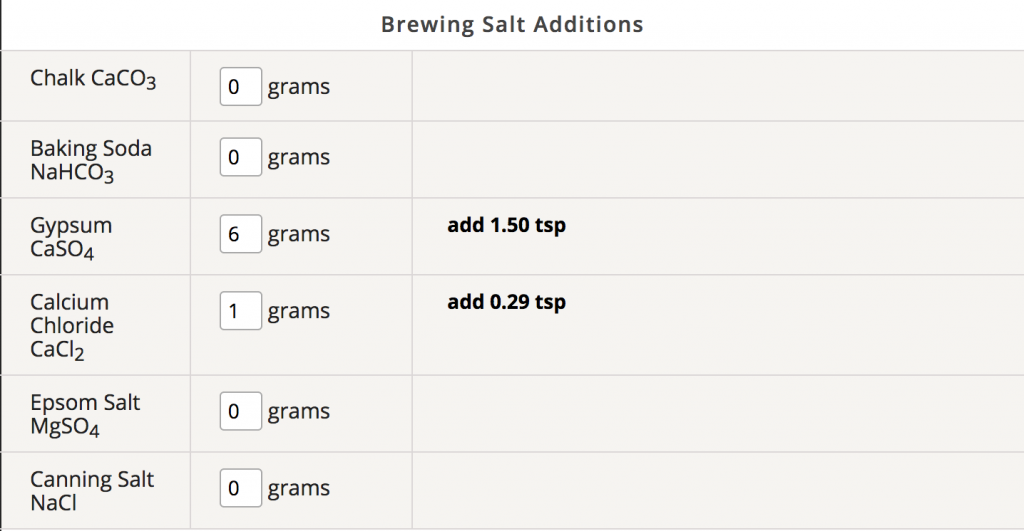

Treat water with 2 tsp calcium chloride, 1 tsp gypsum. Mix all grains dry in bucket before pouring in, Stir in grains into 5 gal of strike water and add ½ tsp of amylase enzyme. Mash at 154⁰F for 1 hour, raise to 163 for 30 minutes, sparge out with 2.5 to 3 gallons of 170⁰F water with same ratio of calcium chloride and gypsum (In this instance you would use 3/5 of your original measurements- since we’re sparging with 3 gallons). You should have a pre-boil gravity of about 1.03-1.045.

Ferment 2 weeks at 55⁰F. I transferred to the lager fridge when gravity was 1.010. Dry hop three days before pulling the beer out. I let it lager for just about a month between 36-38⁰F.