Yeast Washing 101

Saturday, January 30th, 2010Yeast washing is a simple, yet useful procedure that will allow you to harvest, store, and re-use yeast from your own yeast bank for pennies per brew session. Please review how to make a starter and why a stir plate to help you best re-activate your yeast after cold storage.

SANITATION: You must sanitize everything in this process! Storing yeast successfully is fully dependent on keeping the samples pure.

YEAST STOCK: You will harvest the yeast that you are about to wash and store from a recently (same day) emptied fermenter. This yeast cake or slurry will be the basis for all that you are about to do. This is the yeast that will go on to propagate new colonies in future brews. See Fig 1

Fig 1.

HARVESTING: After racking the fermented beer from atop a yeast cake, there will generally be some liquid left along with the yeast cake. Swirl this around and loosen the yeast cake so that you can pour the slurry (sometimes chunks) of yeast into a sanitized flask or 1 gal. carboy. You want plenty of spare volume. Your yeast slurry will be full of trub, some break material, and hop particles. Currently, it is probably looking VERY thick and has no defined layers, though we are about to fix this! Fig 2

Fig 2.

WASH: You will want to have about a half gallon (ample amounts) of boiled and cooled water on hand (so we don’t cook the yeast). In your flask or carboy use enough of this water to double or triple the volume of the slurry that you currently have. Give it a few swirls to mix all of the contents (slurry and water) together. Cover with sanitized foil. See Fig 3

Fig 3.

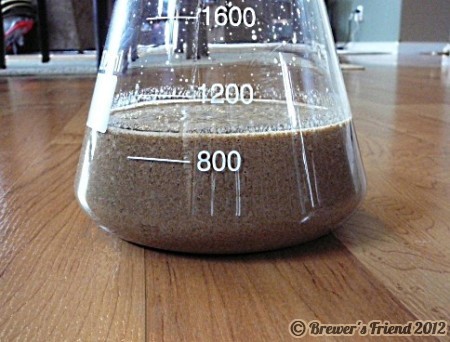

WAIT: Given as little as 15-20 minutes to sit, you will be able to see some drastic stratification in your slurry. The heavier particles, trub, and break material will settle out quite quickly, leaving a dark layer with progressively lighter layers above it. Atop these dark layers you will have a creamy layer of liquid. This is what you want, water and yeast in suspension. See Fig 4

Fig 4.

SEPARATION: You will want to have several sanitized jars available to decant this creamy, yeast filled liquid into. Pour the creamy liquid containing the suspended yeast off of the sediment and into as many jars as it takes to hold it. Now you will have 2-4 jars full of this creamy looking liquid that you will place sanitized lids on, and then place into the refrigerator. See Fig 5. After some time has passed in the fridge you will see that the liquid is now much clearer and there is a nice bright layer of clean yeast at the bottom of each jar. See Fig 6

Fig 5.

Fig 6.

STORING: If your sanitation practices are good, you can store this yeast for months. The yeast should remain in these jars, sealed and refrigerated, until you are ready to make a yeast starter to awaken them. It would also be a good idea to mark these jars with the yeast name, the date, and R1, for “reuse #1”, This way you can keep track of how many times you have re-used this yeast. See Fig 7. Typically after repeated uses the yeast will begin to mutate and its characteristics may change to a degree. You can typically feel confident re-using yeast 4-5 times before degradation is detected.

Fig 7.

RE-USING: When you would like to re-use this strain of yeast, simply allow a single jar of washed yeast to gradually warm to room temperature, decant the liquid and pitch the washed slurry from the bottom of the jar into some new starter wort. See how to make a yeast starter HERE.

IMPORTANT NOTES:

- You can NEVER be too careful with sanitation when it comes to yeast washing/storing.

- Do use a large clear glass container (large flask or 1 gal. carboy) for the HARVESTING and WASH steps in the process.

- Ball or Mason jars make excellent containers for the WAIT and STORAGE steps in the process.

- Be sure to sanitize the jar lids before securing them and storing your yeast.

- Mark your jars with the yeast name, the date and the reuse/generation number (R1, R2,…) and so on to keep track of how many times you have washed this yeast and re-used it.

Update 11/12/2011: Check out the article on Bad Batches to see why you might want to avoid re-pitching yeast, or if you do so, make sure to understand the risks involved.