Brewing Water Basics – Putting it All Together

Tuesday, February 13th, 2018We’ve covered some of the basics of water chemistry in the last two articles, and now we are ready to put it all together.

The first step is to start with chlorine-free water of suitable quality for brewing and reducing the alkalinity if needed.

Once you have an understanding of targeting an optimum range for the mash pH and taken steps to use non-alkaline water for sparging, the next step is to consider using brewing salts in the water to further enhance the flavor of your beer.

Just as in cooking certain spices go well with certain foods, certain brewing salts can enhance certain styles of beers. Looking back at the list of our brewing salts, we can see what each of them brings to the table:

Calcium (in Gypsum and Calcium Chloride): Calcium is the primary ion that determines hardness of the water. It helps with lowering the pH during mashing, helps with precipitations of proteins in the boil (hot break), enhances yeast flocculation, and assists in preventing beerstone. Many lagers are made with very low levels of calcium, so it is not required but can be helpful in the amounts 50-100 ppm.

Magnesium (Epsom Salt or MgSO4): Also responsible for providing hardness to the water, it can provide a sour/bitter flavor to the beer in amounts of 30 ppm or more. It has a laxative effect in much larger amounts. Malt provides all of the magnesium required for yeast health, so it is not required as an addition unless adding sulfate in the presence of a high calcium level (using epsom salts, or MgSO4).

Sulfate: Sulfate is the ion that is used to accentuate hop bitterness by enhancing the dryness of the finish. Additions are normally avoided in continental lagers or only used in small amounts, often 30 ppm or less, and in most ales the ideal amount is 30-70 ppm. For highly hopped beers, the desired sulfate level may be much higher: 150-300 ppm for IPAs or west coast APAs. That will make the finish seem more crisp and dry. If using 150 ppm or higher, the chloride level should be under 50 ppm to avoid a minerally finish to the beer.

Chloride: Chloride accentuates a fullness or “roundness” of flavor in the beer, enhancing the malt sweetness. It is generally used in the 40-100 ppm range in many beers, but in the New England IPA style, the chloride is often over 100 ppm, up to 150 ppm.

Sodium (Non-iodized table salt or NaCl): Sodium rounds out the malt flavors, and can be used in modest amounts (under 150 ppm). A higher concentration can make the beer taste salty, and having a high sodium combined with a high sulfate level can create a harsh bitterness. It is generally recognized that keeping the sodium at 0-60 is a safe bet, and using brewing water sourced from a water softener is to be avoided.

Baking Soda (NaHCO3 or sodium bicarbonate): This is used if alkalinity is needed to raise mash PH, and also provides sodium.

Many of us can remember the older guy at the bar with a tap beer in front of him using a salt shaker to sprinkle salt in his beer. Looking at the list, we can see that the table salt consists of NaCl- both sodium and chloride. The sodium rounds out the malt flavor, and the chloride accentuates the fullness of the malt sweetness. We can do the same thing via these salt additions to the mash and/or preboiled wort.

Determining Brewing Water Additions

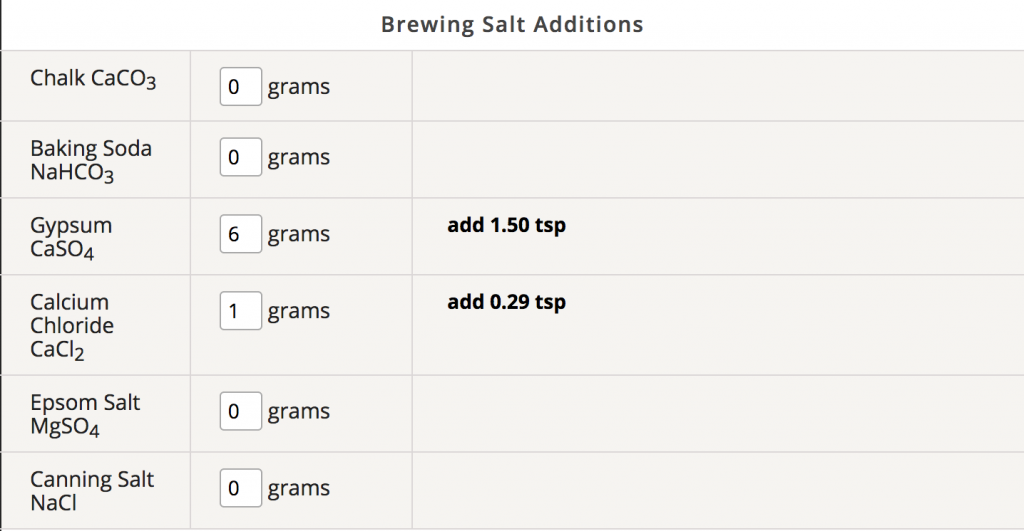

Adding the salts is done in very small amounts, typically grams. While it can be converted to other measurements (a teaspoon of calcium chloride is close to 5 grams), the amounts are generally very small so a scale that weighs to grams and/or tenths of a gram is very helpful. While it is easiest to just add a teaspoon or a half of a teaspoon of something to the mashing water, it’s best to look at a brewing spreadsheet showing the additions so you can see the results of adding the salts. There are also nomographs available and of course an enterprising brewer can calculate it by hand. The amounts are usually expressed in parts per million (PPM) and the spreadsheets themselves have guidelines on how much to add to avoid overuse. The salts are typically added to the mash, but can be added to the boil kettle in some cases. Make sure to never add baking soda or other alkalinity to the sparging water. In the rare case where you need to raise the mash pH, add the baking soda to the mash.

When deciding what additions are suitable for each batch of beer, consider what you want to bring out in the beer’s flavor. Also, keep in mind that “less is more” generally applies, until you know what you like in a certain beer recipe or style. For example, if you are making an American IPA you may want to use some gypsum (calcium sulfate), as the sulfate will help to provide a dry finish and a crisper mouthfeel to enhance the hops bittering. While some brewers will go up to 300 ppm of sulfate in these beer styles, you may want to start smaller at first to avoid perceptions of harshness. Since the easiest way to add sulfate to the beer is via gypsum which also adds calcium, this is commonly done. The other way to add sulfate is via magnesium sulfate (epsom salt), but it’s important to keep the magnesium level below about 30 ppm to avoid a bitter/sour flavor. Some brewers eschew the addition of epsom salts totally, feeling that the gypsum does the job without any issue.

For a beginning profile for something like an American pale ale or IPA, a modest addition of gypsum is may give great results. As an example, using 7 gallons of RO to begin the brewday for a 5 gallon batch, adding 7 grams of gypsum will provide 63 ppm of calcium and 148 ppm of sulfate. Looking at the list above, you can see that it is in a desirable range for both calcium and sulfate for a hoppy beer. Using a brewing spreadsheet, you can see that using this amount of gypsum in the mash is also likely to give an optimum mash pH as well, depending on the grainbill, so this is a great place to start. After the brew is finished and taste testing, a decision can be made for next time. You can even add a touch of gypsum to the glass, to see if you prefer the beer with more sulfate for next time. Starting with less than the maximum recommended generally gives satisfaction to the brewer.

For beers that have a lovely malt flavor, calcium chloride is a common addition. Looking at the list again, you can see that calcium chloride will provide calcium to the mash as well as the chloride. Since chloride enhances the fullness or “roundness” of malt flavor, and gives a perception of sweetness to the malt, adding it to a beer recipe can bring the flavor to the next level. If you’re making an Octoberfest or brown ale, adding some calcium chloride would be a great move. Adding 3 grams to a 5 gallon batch of brown ale maybe be just the ticket to making a very good beer great.

For brewing lagers, especially European style lagers, less sulfate is desirable and often it is completely left out. It wouldn’t be unusual to brew a German pilsner without any additions to RO water at all, so keep in mind that adding brewing salts is not necessary and is a matter of the style of the beer as well as the brewer’s taste.

For a good basic “all purpose” water profile to start, consider something like this:

Calcium: 75 ppm

Magnesium: 10 ppm (more or less, but under 25 ppm)

Sodium: 0-50 ppm

Sulfate: 50-70

Chloride 50-70

Mash pH of 5.3-5.5

There are a couple of cautions when adding brewing salts to your water adjustments. Many brewers will refer to the sulfate:chloride ratio because that’s been discussed in older brewing texts. The theory is that keeping a ratio of sulfate to chloride will make a beer more “hoppy” or more “malty”- but this is not so. When discussing a ratio, remember that 80 ppm of sulfate and 40 ppm of chloride is a 2:1 ratio, and according to a brewing water spreadsheet available online (EZ Water) the text says “may enhance bitterness”. That’s great- but 800 ppm sulfate and 400 ppm of chloride is ALSO a 2:1 ratio- and it also says “may enhance bitterness”. Common sense dictates that one beer will be far different than the other, while the ratio is exactly the same. The first should be just fine, although not with a particularly dry finish, but the second will be “minerally” and undrinkable. When you are cooking and add too much salt to your spaghetti sauce ,you cannot erase that by adding more pepper. When brewing, you also can’t “erase” too much gypsum by adding more calcium chloride. Instead of targeting a sulfate:chloride ratio, look at the actual numbers in ppm and the recommended limits of each ion, and make the decision based on that.

Another pitfall is to be so consumed with the numbers of the ions is to forget that the mash pH is the most important aspect of delving into water chemistry. An appropriate mash pH will provide the most benefit to your beer, while the flavor ions are the “seasonings” in your beer. Starting with a good recipe and using good water and targeting an optimum mash pH will make a very good beer. Tweaking the recipe by adding some gypsum and calcium chloride (as examples) may take that very good beer to very, very good or even excellent beer. To compare brewing to cooking again, adding the perfect amount of salt and pepper to your spaghetti sauce can make your very good sauce something memorable, and adding a bit of rosemary may make it exceptional. So it goes with brewing- starting with a great base and adding your brewing salts in the right amounts can take it to the next level. Adding too much is more of a danger than too little, so be aware of that in your additions as you start adjusting your water.

Entire books have been written about brewing water and water chemistry for brewers, as the subject is complex. Further reading is highly recommended. Some good sources are listed below:

Here are a few links to additional reading, as well as some of the sources of this article:

https://howtobrew.com/book/section-3/understanding-the-mash-ph/reading-a-water-report

John Palmer, How To Brew

https://sites.google.com/site/brunwater/water-knowledge

Martin Brungard, Bru’nwater

https://braukaiser.com/wiki/index.php?title=Beer_color,_alkalinity_and_mash_pH

Kai Troester

https://www.brewersfriend.com/mash-chemistry-and-brewing-water-calculator/

Brewer’s Friend, water calculator

Water- A Comprehensive Book for Brewers John Palmer & Colin Kaminsky

Sorry, comments for this entry are closed at this time.